Eugène Anatole Carrière

(Gournay-sur-Marne 1849 - 1906 Paris)

Fillette endormie, c. 1897

Oil on canvas, 24.5 x 32 cm

Signed and inscribed upper left: Eugène Carrière à Gustave Geffroy son ami

(scratched into the dry paint)

Provenance:

Gustave Geffroy, Paris;

Eric Ledoux, Paris;

Patrick Roger-Binet, Paris;

Private collection, New York.

Literature:

Gustave Geffroy, L’Œuvre de Carrière, Paris 1902, repr. p. 10;

Anne-Marie Berryer, Eugène Carrière. Sa vie, son œuvre, son art, sa philosophie, son enseignement, Liège 1935, no. 236;

Robert J. Bantens, Eugène Carrière, Ann Arbor 1983, p. 260, no. 233, repr. p. 743

Véronique Nora-Milin and Alice Lamarre, Eugène Carrière 1849-1906. Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint, Paris 2008, p. 250, fig. 787.

Eugène Carrière’s sleeper engages the viewer in an indiscreet, almost voyeuristic way. The monochrome brown palette invests the scene with an unreal quality. It is almost as if the viewer can see the sleeping girl dream[1] – a highly characteristic Symbolist motif. The Symbolist painters active around 1900 sought to interpret spirituality in visible terms, entering into a dialogue with nascent psychoanalysis and the interpretation of dreams. The writer Theodor Wolff, Berliner Tageblatt correspondent in Paris, noted in his diary in 1908: ‘Carrière went after the inner light, he wanted to let this inner light shine forth in the fullness of its power and beauty, and he therefore suppressed everything that impaired the revelation of this light. He suppressed the external brilliance of color, everything that would attract the eye and distract the senses, creating a distinctive gray haziness through which the soul – like a fine vapor on an October day – gently wafts.’[2]

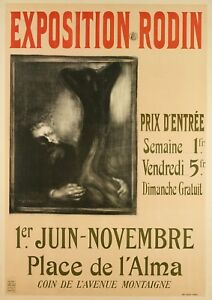

Fig. 1: Eugène Carrière, Poster for the ‘Exposition Rodin’, 1900, lithograph, Musée Rodin, Paris, inv. Af. 106-1.

In the 1880s, Carrière took up camaïeu painting, a tonal technique that he favored for his portraits of sleepers. His subjects emerge dreamlike from a vague, often undefined background. It is conceivable that these monochrome works have their direct counterpart in dream research findings. Early dream research well predating the arrival of color film suggested that the majority of dreams were in black and white. Later studies have suggested that exposure to Technicolor and color TV has conditioned most people to dream in color.[3] Today, Carrière’s oeuvre has largely lingered in obscurity. But in his lifetime, his work was highly valued both by his fellow artists and by the public. He enjoyed a close friendship and artistic relationship with Auguste Rodin and many contemporary critics saw him as Rodin’s equal. His diffuse, highly atmospheric camaïeu paintings were compared to Rodin's sculptures with their nuanced effects of light, because Carrière, like Rodin, avoided color. The portraits emerge from an undefined background and recall the smooth forms of Rodin’s sculptures which seem to detach themselves from the unhewn block of marble. The writer and art critic Camille Mauclair (1872-Paris-1945) insightfully noted: ‘Rodin paints in marble, Carrière sculpts in shadow.’[4] The two artists held each other in high mutual regard and Rodin was to entrust the younger man with the poster for his first major retrospective exhibition (Fig. 1).

This painting is inscribed: Eugène Carrière à Gustave Geffroy son ami – a gift of the artist to the writer and critic Gustave Geffroy (1855–1926), a leading figure in the cultural life of Paris and friend of Rodin, Monet and Cézanne. He was the compiler of the first catalogue raisonné of Carrière’s work. Carrière was one of the foremost representatives of French Symbolist art. His unconventional style influenced pictorialism in photography. Active between 1900 and World War I, the pictorialists experimented with soft-focus and blurred line.[5] The Danish Symbolist painter Vilhelm Hammershoi, creator of poetic, hauntingly still interiors characterized by their spareness and muted, almost monochromatic tones, would almost certainly have seen paintings by Carrière on his visit to Paris in 1891-2.

Fig. 3: Sleep, 1890, oil on canvas, 66.2 x 82.3 cm, signed lower left: Eugène Carrière, Staedelmuseum, Frankfurt, inv. 2414.

Carrière trained at the Ecole Municipale de Dessin in Strasbourg while serving an apprenticeship in lithography. In 1870 he moved to Paris, intending to further his training at the École des Beaux-Arts but when the Franco-Prussian War broke out he interrupted his studies to sign up as a volunteer for the army. He was taken prisoner at Neuf-Brisach and transferred to Dresden where, somewhat surprisingly, he was given the opportunity to visit the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister. His encounter with the works of Rubens and Velazquez was to shape his early career.[6] After the war he returned to Paris and between 1872 and 1876 studied under the tutelage of Alexandre Cabanel (1823–89). It was not until the 1880s that he took up camaïeu painting, a technique that employs two or three shades of a single color to create a monochromatic image. Mauclair described Rodin’s and Carrière’s works as ‘statuary and painting transformed into arts of psychological expression’.[7] In 1890, the two friends joined the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts.[8] In 1898, Carrière opened an art school – the École Carrière – where his pupils included Henri Matisse (1869–1954) and André Derain (1880–1954).

Fig. 2: Tête de jeune fille endormie, c.1902, oil on canvas, 36 x 47 cm, signed lower left: Eugène Carrière, The Pushkin Museum, St. Petersburg.

Carrière was not interested in commissioned work. He concentrated on portraying friends and family. Among his subjects were important literary figures such as Geffroy, Edmond de Goncourt (1822-96), Alphonse Daudet (1840-97), Paul Verlaine (1844-96) and leading artists such as Paul Gauguin (1848-1903).[9] His wife and children were his preferred models for a group of psychological portraits which he dubbed Maternité. He repeatedly turned to the motif of the seemingly unobserved but observed sleeper and dreamer (Figs. 2 and 3).

-

Jane R. Becker, A Cross-Media Kinship. Auguste Rodin and Eugène Carrière, The Met, December 11, 2017 <https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2017/auguste-rodin-eugene-carriere> (accessed January 19, 2022).

- Theodor Wolff, Pariser Tagebuch, Munich 1908.

-

The Scottish researcher Eva Murzyn, of the University of Dundee, examined various aspects of dream research and the color of dreams in a study published in 2008; see Murzyn, ‘Do we only dream in colour? A comparison of reported dream colour in younger and older adults with different experiences of black and white media’, in Consciousness and Cognition, XVII/14, Amsterdam 2008, pp. 1228-37. <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1053810008001323?via%3Dihub> (accessed February 2, 2022).

-

Camille Mauclair, ‘Rodin peint en marbre, Carrière sculpte en ombre’, cited in Auguste Rodin – Eugène Carrière, exhib. cat., Musée d’Orsay, Paris 2006.

-

Kristina Lowis, Eine Ästhetik der Kunstphotographie im internationalen Kontext (1891-1914), Düsseldorf 2003, p. 212.

-

Robert James Bantens, Eugène Carrière. His Work and His Influence, Ann Arbor 1983, p. 15-16.

-

Camille Mauclair, ‘La psychologie du mystère’, in Les Maîtres artistes, I, Paris 1901, p. 45.

-

Bantens, op. cit., 1983, p. 79.

-

Véronique Nora-Milin and Alice Lamarre, Eugène Carrière 1849-1906. Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint, Paris 2008.