Vilhelm Hammershøi

(1864 - Copenhagen - 1916)

Interior - Pigen dækker Bord (The Maid Setting the Table), 1895

Oil on canvas, 97 x 70 cm

Provenance:

Alfred Bramsen (1851-1932), Copenhagen (purchased from the artist in 1896)

By inheritance to Karen Bramsen (1877-1970, daughter of Alfred Bramsen) and Gustav Falck (1874-1955, Bramsen’s son-in-law)

Copenhagen, Winkel & Magnussen, auction sale 182, 28 October 1935, lot 54

Mrs Magda Rothschild, Copenhagen (purchased at the above sale)

Normi Rothschild (1932-2012), Copenhagen (daughter of Magda Rothschild) Copenhagen, Winkel & Magnussen, auction 352, 30 March 1949, lot 256 (consigned by Normi Rothschild, bought in)

With Hjalmar Kleis, Copenhagen

With H. Axelsen, Copenhagen

Copenhagen, Winkel & Magnussen, auction sale 360, 21 June 1950, lot 64 (consigned by H. Axelsen, bought in)

Copenhagen, Kunsthallen, auction sale 175, 9 May 1951, lot 168

Copenhagen, Bruun Rasmussen, auction sale 383, 3 October 1978, lot 58

Unidentified auction sale, 20 February 1979, lot 70

Åmells konsthandel, Stockholm (by 1988)

Olof Lagercrantz (1911-2002), Drottningholm (purchased from Åmells konsthandel in 1989)

Richard Lagercrantz (b.1942), son of Olof Lagercrantz

Private collection, Stockholm

Exhibited:

Den Fri Udstilling [‘The Free Exhibition’], Copenhagen 1895, no. 15

Arbejder af Vilhelm Hammershøi, Kunstforeningen, Copenhagen 1916, no. 120

Nyere dansk kunst, Liljevalchs konsthall, catalogue 20, Stockholm 1919, no. 428

Udvalg af Vilh. Hammershøis arbejder, Kunstforeningen, Copenhagen 1930, no. 6

Vilhelm Hammershøi, Theodor Philipsen, L.A. Ring, Sveriges Allmänna Konstförening, Stockholm 1930, no. 11

Från atelier till plein air, Åmells konsthandel, catalogue 15, Stockholm 1988, no. 10

Literature:

Sophus Michaëlis and Alfred Bramsen, Vilhelm Hammershøi, Copenhagen 1918, p. 92, no. 142

Poul Vad, Vilhelm Hammershøi – Værk og liv, Copenhagen 1988, p. 147

In 1892, after a honeymoon spent in Paris, Hammershøi and his wife Ida Ilsted (1869-1949) moved into a rented apartment in a villa named Ny Bakkehus in Frederiksberg near Copenhagen. Here they stayed until 1897, when the building was demolished. During this five-year period Hammershøi’s time was still largely occupied with portraits, figure paintings, cityscapes and landscapes, while scarcely a dozen interiors depicting the couple’s apartment and the shared hall of the villa are known.

The present painting is a fine example of Hammershøi’s early interiors. It is marked by a more refined use of color than in his later work. Here, he explores the reddish tone of the large, centrally placed mahogany armoire as a means of offsetting the startling crisp white of the table cloth. The narrow pictorial space, too, is typical of his other Ny Bakkehus interiors, in which the picture plane is often placed parallel to the back wall and the furniture. He has nevertheless succeeded in creating a powerful, almost exaggerated three-dimensionality by allowing the lower edge of the canvas to crop the front legs of the table. The result is an almost stage-like effect that makes these early interiors so markedly different in spatiality from the more numerous interiors showing Hammershøi’s later home at Strandgade 30.

In this restricted spatial setting, the furniture and the female figure are the sole conveyors of psychological content. Hammershøi – revealing himself as a true member of the Symbolist movement – regarded items of furniture as enigmatic substitutes for human presence. The imposing armoire seems to stand for a kind of petrified emotion which is itself mirrored in the closed expression of the figure setting the table, while her absent, introspective gaze is reiterated by the three boarded-up windows which loom as dark voids in the wall behind.[1] The same modest pieces of furniture would reappear continually in Hammershøi’s interiors – like actors playing different roles. The figure of the young woman – modelled on his wife Ida, his model in a great many of his paintings of interiors – was also a recurrent motif. That furniture should play as important a part as the figure inhabiting the room is a hallmark of Hammershøi’s art. Even so, the celebrated Swedish writer, critic and publicist Olof Lagercrantz – a former owner of the painting – noted that in it he had finally found a work by Hammershøi in which the female model did not simply try to melt into her surroundings. “At least,” he said, “we seem to glimpse a true individual.”[2]

Hammershøi entered the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Art in Copenhagen in 1879, completing his studies in 1885. In the same year he made his first appearance at the Academy’s annual Charlottenborg Spring Exhibition, entering a portrait of his sister. The failure of the painting to receive a prize caused outrage among his fellow artists. In 1888, another portrait of his sister was turned down by the jury of the Spring Exhibition. This gave rise to the establishment of the first (and very modest) Salon des Refusés in Denmark. And when, two years later, one of Hammershøi’s early interiors was also turned down by the jury, his art once again became the rallying point for rebellious young artists. Out of this emerged the artists’ association known as Den Frie Udstilling [‘the Free Exhibition’], which was set up in 1891, with Hammershøi as a founding member. Den Frie Udstilling soon became the primary venue for Symbolist art in Denmark.

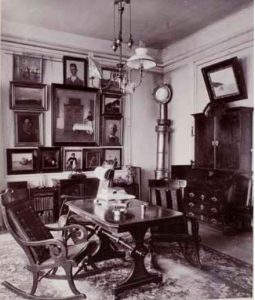

Pigen dækker Bord is one of only two paintings that Hammershøi exhibited at Den Frie Udstilling in 1895. An anonymous critic, writing under the pseudonym ‘Avant-garde & Co.’ in the Danish daily newspaper Politiken, praised it for its “wealth of finely tuned grey and white notes that are a true feast for the eyes”.[3] Another critic noted its “wonderfully fine and melancholic mood”.[4] Despite the initial success of the painting, Hammershøi appears to have returned to it for final retouching, or overpainting in part to alter the composition – the faint silhouette of a second chair can be detected at the left of the armoire.[5] On completion, he sold it to his most loyal patron, the dentist Alfred Bramsen (1851-1932).[6] The price was 275 kroner, at the time a little more than average for an interior by Hammershøi. Over time the Bramsen collection would become something of a showroom for Hammershøi’s art, often visited by foreign collectors, critics, writers and artists. A photograph taken of Bramsen’s living room in 1898 shows an array of paintings with Pigen dækker Bord as the centerpiece (fig. 1).[7] Although he would occasionally sell a work, Bramsen kept this painting for the rest of his life and included it in the exhibitions of works by Hammershøi that he organized in 1916 and 1930.

From the second half of the 1890s onwards – partly thanks to the tireless support of Bramsen – Hammershøi enjoyed ever greater success abroad. In 1895, he exhibited with the Freie Vereinigung Münchner Künstler at the Kunst-Salon Gurlitt in Berlin, and two years later Serge Diaghilev included paintings by Hammershøi in a Scandinavian show in St Petersburg. In 1905, the influential Berlin-based art dealer Paul Cassirer purchased several of Hammershøi’s paintings and staged a one-man show of his work at the Hamburg branch of his gallery. In between, Hammershøi took part in a number of major exhibitions in France, Germany, Italy, England and the United States. After his death, however, his oeuvre lapsed into obscurity and was only rediscovered in the 1970s with the critical re-evaluation of Symbolism. Exhibitions in Europe and Japan followed, the most recent being the major retrospectives staged in Munich in 2012 and in New York, Toronto and Seattle in 2015-16. Hammershøi is today regarded as the leading Danish artist of the second half of the nineteenth century.

Text by Dr. Jesper Svenningsen, Copenhagen

[1] The room is described in this way by Alfred Bramsen, who undoubtedly visited Hammershøi there.

[2] Lagercrantz’s comment is to be found on a note on the stretcher. He owned the painting for over ten years.

[3] Politiken, 30 March 1895.

[4] Social Demokraten, 30 March 1895.

[5] The surmise that Hammershøi altered the painting after its first exhibition is supported by notes made by Hammershøi’s mother in her scrapbooks (now in the Hirschsprung Collection, Copenhagen).

[6] According to the notes made by Hammershøi’s mother. The date of the sale is given as 1896.

[7] See Jesper Svenningsen, Hammershøiana. Tegninger, fotografier og andre erindringer. Drawings, photographs and other memories, exhib. cat., The Hirschsprung Collection, Copenhagen 2011, repr. p. 29.