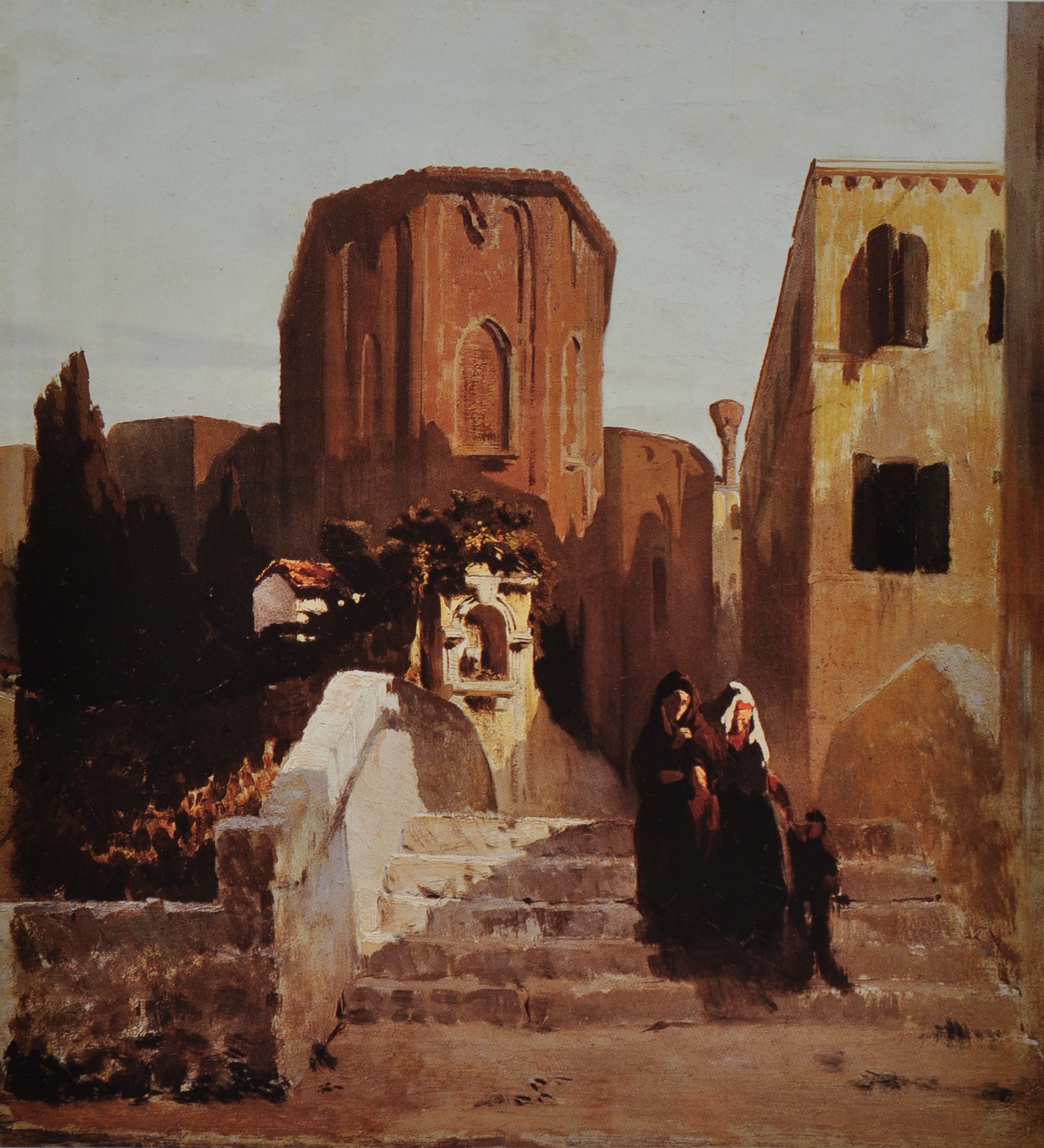

Telemaco Signorini (1835 - Florence - 1901)

Villa presso Firenze (Villa near Florence), c.1856-9

Oil on cardboard, 21 x 17 cm

On the back collector’s stamp of Paolo Signorini; printed card of the Galleria Pesaro in Milan; typewritten note with number or reference (37)

Provenance:

Collection Comm. Paolo Signorini, Florence

Exhibitions:

Onoranze a Telemaco Signorini, exhib. cat., Florence, Accademia di Belle Arti, 1926, p. 23 no. 5

Esposizione e vendita delle opere di Telemaco Signorini e delle opere di altri artisti dell’800 dagli stessi donate a Telemaco Signorini, exhib./auction cat. with introduction by U.Ojetti Milan, Galleria Pesaro, 1930, pl. CXII, no. 78

Macchiaioli a Montepulciano, Capolavori e inediti privati, exhib. cat. Montepulciano, Museo Civico Pinacoteca Crociani, 2010, pp. 48, 108, no. 13

Macchiaioli a Villa Bardini, exhib. cat. Florence, Villa Bardini, 2011, pp. 48, 108,

no. 13

Literature:

Telemaco Signorini, exhib. cat., Milano, 1942, p. 97

Telemaco Signorini (1835-1901) was one of the major protagonists of the Macchiaioli, a group of Italian realist painters active in Florence at the time of the Risorgimento and united by their wish to reinvigorate Italian art.[1] Born as the son of a renowned Florentine veduta painter, Signorini started his artistic training early in life. At the age of twenty he started to frequent the Caffè Michelangelo where progressive artists gathered to discuss politics and art. In 1855 the painters Domenico Morelli, Saverio Altamura and Serafino De Tivoli met there and enthusiastically reported on the novelties of French romanticism and the Barbizon painters they had just seen at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. A year later the Florence based Russian nobleman Anatole Demidoff allowed artists access to his art collection, which included works by major French painters like Paul Delaroche, Eugene Delacroix, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps. These left quite an impression on Signorini and his peers and inspired them to further experiment with technique and subject matter. The Neapolitan Morelli had introduced his Florentine colleagues to a sketchy brushwork and strong chiaroscuro, which he applied to the bozzetti for his history paintings. Signorini and several others started to experiment with Morelli’s practice en plein air, which led to the macchia (=spot) technique the group would become known for. Pictorially speaking, the macchia translated subject matter into painting by juxtaposing spots of different tonal values and light intensity, which defined shapes without the need of outlines. The earliest examples of this practice are the sketches of streets, canals and palazzi Signorini made during his first visit to Venice in 1856 (fig. 1). Returning to Florence later that year he wanted to exhibit two of these works at the Florentine Promotrice (the major annual art exhibition in Florence), but the jury rejected them for their “excessive violence of chiaroscuro” as Signorini recorded retrospectively in a letter from 1892.[2] Exaggerated contrasts, the disregard of disegno in favour of effect and a sketchy quality of the works shown by Signorini and his peers in the second half of the 1850s led the moderate-conservative critic Giuseppe Rigutini to deridingly label the group “Macchiaioli” in 1862.[3] Signorini defended the new practice explaining that the experimental technique and realist subject matter were means to develop a novel way of representing the current times characterized by transition in the realms of politics, economy and society. He also pointed out that the exaggerated chiaroscuro had been an important step in developing the macchia but had now given way to a more subtle modelling of tonal values.

Fig. 1 Telemaco Signorini, Il Ponte della Pazienza a Venezia, 1856, oil on canvas, 39 x 36 cm, private collection

The sketch of the Villa presso Firenze, like Signorini’s Venetian sketches (fig. 1) and some other works from the second half of the 1850s, are typical testimonies of the early macchia practice and show Signorini’s fascination with strong contrasts. Dabs of light and dark greens define trees and smaller plants that stand out against the light walls of the villa. The shadows cast by the roof are rendered in a dark bluish-grey, evidence for Signorini’s ability to closely observe nature and translate his perception into paint. A typical example for his capability to abstract objects to their essence is the way he adumbrated the terracotta pots along the path with minimal means. The vivid brushwork, intelligent incorporation of the support in the foreground and seemingly incidental cropping reminiscent of contemporary photography, add to the sense of immediacy emanating from this fresh oil sketch.[4]

In many ways a typical Tuscan villa with its characteristic colouring, three storeys and arched loggia, the building in this sketch can be identified with the country house which features in the background of the portrait Antonio Ciseri painted of the world famous Florentine pietra dura artist Gaetano Bianchini and his family.[5] The reminiscence becomes even more obvious in a preparatory drawing for the family portrait (fig. 2). It clearly shows the unusual non-axial order of the windows and the distinctive opening in the wall between the ground- and first floor near the right corner of the main building that also characterize the villa in Signorini’s sketch. Due to the lack of source material the nature of Signorini’s ties with the Bianchini family cannot be verified. Yet, attempts to shed light on this question point to the tightly knitted dynamic artist network in 19th-century Florence that generated traditional art and artefacts as well as being a platform for such innovative works as Signorini’s sketch of the villa Bianchini.

[1] The most notable artists of this movement besides Telemaco Signorini were Giuseppe Abbati, Cristiano Banti, Odoardo Borrani, Vincenzo Cabianca, Adriano Cecioni, Vito D'Ancona, Serafino De Tivoli, Giovanni Fattori, Raffaello Sernesi and Silvestro Lega.

[2] “Al mio ritorno in Firenze, ebbi i miei primi lavori rigettati dalla nostra Promotrice per eccessiva violenza di chiaroscuro e fui attaccato dai giornali come macchiajolo.” Letter from Signorini sent to the President of the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze, 1892; Alba del Soldato, „Cronaca Biografica e Storica“, in Telemaco Signorini, exhib. cat., ed. by Piero Dini, Montecatini Terme 1987, p. 54.

[3] “Già da qualche tempo si parla fra gli artisti di una nuovo scuola che si è formata, e che è stata chiamata dei Macchiajoli. [...] Son giovani artisti ad alcuni dei quali si avrebbe torto negando un forte ingegno, ma che si son messi in testa di riformar l’arte, partendosi dal principio che l’effetto è tutto. [...] Che l’effetto ci debba essere, chi lo nega? ma che l’effetto debba uccidere il disegno, fin la forma, questo è troppo.” Giuseppe Rigutini (alias Luigi), “Ciarle Fiorentine”, Gazzetta del Popolo, 3 November 1862, reproduced in Telemaco Signorini, Zibaldone, Florence 2008, s.p.

[4] Signorini and the Macchiaioli had a strong interest in scientific discoveries, optical devices and photography, which shows in their approaches to representing reality. See I Macchiaioli e la fotografia, exhib. cat., ed. by Monica Maffioli, Silvio Balloni and Nadia Marchioni, Florence: Fratelli Alinari Fondazione per la Storia della Fotografia, 2008.

[5] Gaetano Bianchini (1807–1866) worked for patrons in Italy, Russia and the United Kingdom. For more information see Dagli splendori di corte al lusso borghese – L’Opificio delle Pietre Dure nell’Italia unita, exhib. cat., ed. by Annamaria Giusti, Florence 2011.