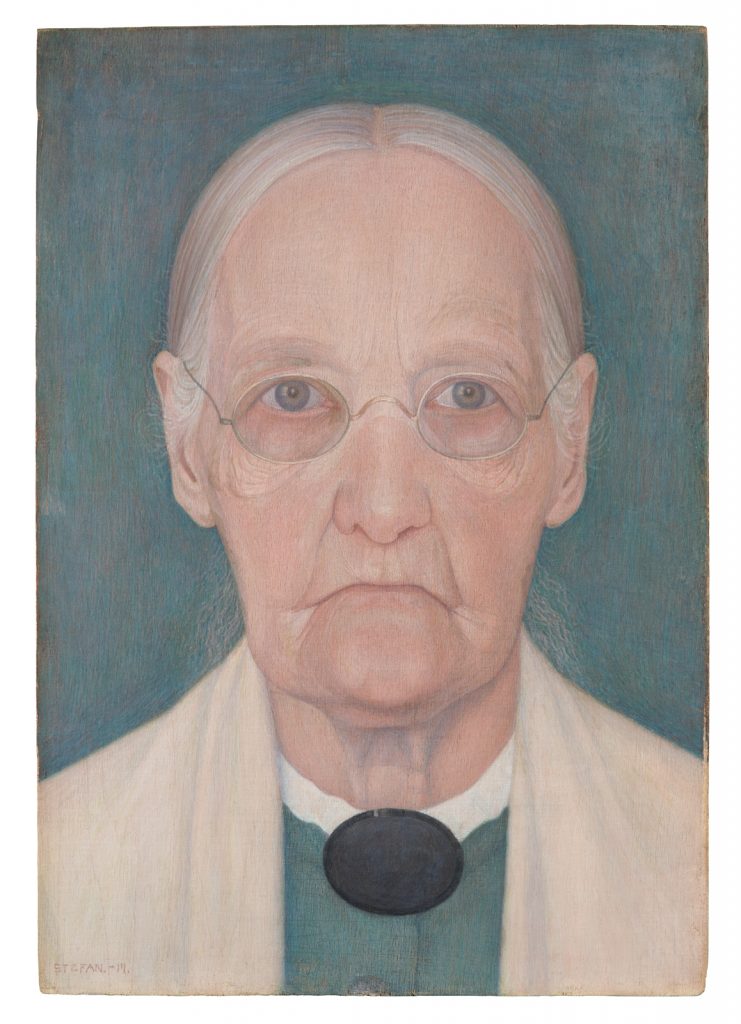

Stefan Johansson

(Vist, Östergötland 1876 - 1955 Karlstad)

”Min mor” (My Mother), 1914

Watercolor and tempera on panel, 19.8 x 13.5 cm

Signed and dated lower left Stefan 14.

Provenance:

1916 with sculptor Erik Rafael-Rådberg (1881-1961);

Private collection, Värmland;

Private collection, New York..

Exhibition:

The portrait might have been shown at the Swedish art exhibition in Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, in November-December 1916. Unfortunately, no information is available on which works Johansson exhibited.

Literature:

Folke Holmér, En bok om Stefan Johansson, Stockholm 1958, ill. p. 35.

We are grateful to Dr. Stefan Hammenbeck, an expert on Stefan Johansson, for his help in compiling this entry and confirming the authenticity of the painting.

Stefan Johansson’s œuvre includes a series of outstanding portraits, mainly of women. As a rule he produced male portraits only of artist friends or others in the art world. They are characterized by a realism that is unrivaled in Swedish art. Johansson had certainly been impressed by Renaissance portraits, but as a member of the progressive artists’ association Konstnärsförbundet, he was also involved in an ongoing dialogue with other artists of his generation. Moreover, he engaged with expressive leanings, such as the work of Van Gogh, which he had already seen in Stockholm in 1898 and again in Cologne in 1912. Yet in his portraiture he finally turned to a brand of realism that made him seem like a forerunner of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity).

The approximately 20 portraits that Johansson painted of his mother, Maria Johansson (1839-1924), occupy a unique place in his artistic production as well as in Swedish art.[1] Maria Johansson, the mother of two sons, Seth (b. 1873) and Stefan (b. 1876), was a teacher. She was apparently strict but fair, and well-liked by her pupils. She sat for her son even before her retirement, but more so afterwards. The long-standing correspondence between Johansson and his mother documents the fruitful exchange of ideas between the artist and his model. The recurrent assertion that Johansson had an abnormally close relationship with his mother, felt her to be overpowering, and lived with her his whole life is based on a misunderstanding. In fact, the mother received a small orphan’s allowance for every family member living in her household. Both sons were officially registered as living with their mother until her death, so that she could continue to claim this money. The intense portrait succeeds in conveying the sitter’s deeply religious nature. It may well be a first study for the large version of 1919, which is now in the Norrköpings Konstmuseum.

In Stefan Johansson’s early portraits of his mother we encounter an active woman, who is usually engaged in household chores. The artist experimented with various sections and formats, until his attention was finally directed at her face, tightly framed, en face or in profile, always painted from life.

The present portrait, Min Mor, depicts the 75-year-old mother as an energetic woman who is nevertheless marked by age. The strict frontal view recalls heraldic portraits. Her hair is tightly parted in the center; wisps of hair curl beside her ears and on her neck. She wears a shawl over her shoulders and a brooch pinned to the collar of her blouse. Her green-blue eyes, enlarged by her reading glasses, look at – if not straight through – the viewer. The fact that this small picture was in the possession of the sculptor Erik Rafael-Rådberg, a friend of the artist, in 1916 suggests that Johansson gave the portrait to his friend as a present.

Stefan Johansson was very reluctant to sell the portraits of his mother, preferring to place them in museums, such as the famous collection of Ernst Thiel, the Thielska Galleriet in Stockholm. The portraits in his estate were divided up, at his request, between the museum of Linköping and the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm.

Even though Johansson’s work is rather curious, it can be placed in the same context as contemporaneous Scandinavian painting – just think of Eugène Jansson, the early Edvard Munch or Vilhelm Hammershoi. Introversion is something these painters have in common, and Johansson shares with Hammershoi the meditative engagement with ever-recurring motifs taken from one’s immediate surroundings.

Johansson’s spirituality is revealed in his art. He devoted himself to a type of mysticism of light. The emanation of light was, in his eyes, a timeless, divine principle. Kandinsky’s Über das Geistige in der Kunst (Concerning the Spiritual in Art) and Okakura Kakuzo’s Die Ideale des Ostens (The Ideals of the East) were crucial to his artistic development. When Johansson died in 1956, Kakuzo’s book and the Bible were lying on his desk.

Johansson disliked the art academy and insisted that his academic training in Stockholm had not had any positive influence on his artistic development. Much more formative, in his view, were the journeys he made between 1909 and 1913 to Germany and especially to Italy, where he had engaged with the painting of the Renaissance and with contemporary Italian art. Works by Johansson were shown in 1911 at the large international exhibition in Rome[2] and in 1920 at the Biennale in Venice.[3]

It is possible that the Old Masters and fresco painting inspired Johansson to develop his unusual painting technique. At any rate, he became enthusiastic about painting in watercolor and tempera on unprimed canvas. For this purpose he used irregularly woven canvas, so-called crepe weave, without a ground, to which he applied watercolor and tempera directly. The optical effect resembles a grid and recalls the paintings of the contemporaneous Italian Divisionists, whose work he had certainly seen in Italy. The artist stuck to this time-consuming technique – which required a long period of drying between every application of paint – until the end of his career.

[1] At least five portraits of Johansson’s mother were destroyed in a fire in his studio in 1913. [2] Exposizione Internationale, Rome, 1911. [3] L'Esposizione internazionale d'arte, Biennale di Venezia, XII, 15 April - 31 October 1920.