Carl Gustav Carus

(Leipzig 1789 - 1869 Dresden)

A Moonlit View of the Artificial Ruin near Schloss Pillnitz

Oil on paper mounted on cardboard, 10.5 x 7 cm

Executed on a printed invitation card from the Dresden botanical association FLORA

Provenance:

- Kunsthandlung Rusch, Dresden (by 1930);

- Kunsthandel Luz, Berlin (by WWII);

- listed by Prause as ‘whereabouts unknown’ (1968);

- private collection, Liechtenstein (documented 1995-2009);

- private collection, Switzerland

Exhibited:

- Dresden, Kunstausstellung Kühl (label on the verso);

- Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum (inv. Gm 2059), on long-term loan from a private collection (1995-2009).

Literature:

Marianne Prause, Carl Gustav Carus. Leben und Werk, Berlin 1968, p. 93, no. 32, repr. (with incorrect measurements)

There is an undeniable magic in moonlight (...).[1] Carl Gustav Carus, Lebenserinnerungen, 1865-6

Carl Gustav Carus’s preferred landscape motifs were, from the early 1830s, subjects sketched before nature in the surroundings of Pillnitz, near Dresden. He was personal physician to the Saxon royal family, who spent their summers in Pillnitz, and this obliged him to be close at hand. He therefore purchased a country property near Schloss Pillnitz in 1832 and regularly set out to explore the local countryside. The present painting was made not far from his house on one of these excursions.

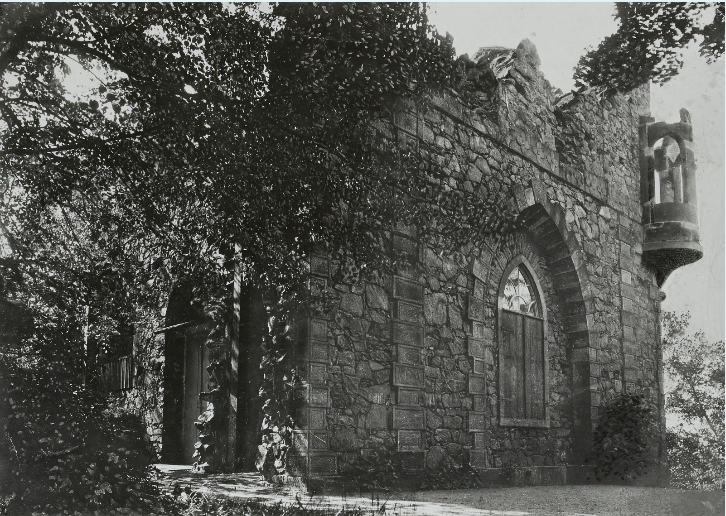

Fig. 1 Johann Daniel Schade’s artificial ruin on the Schlossberg at Pillnitz

The former hamlet of Borsberg[2] with its 350-meter high hill lies on the upper slopes of the Elbe valley north-east of Pillnitz. Around 1780, Kurfürst Friedrich August III ordered part of the Meixgrund (also known as ‘Friedrichsgrund’), a side valley north-east of Schloss Pillnitz, to be landscaped and paths to be laid. An extensive complex of stone bridges, staffage buildings and decorative landscape features was created. Many of these features are still extant. One of the paths led up to the highest point of the Borsberg, where an artificial grotto was constructed. In 1785, an artificial ruin in neo-Gothic style designed by Johann Daniel Schade (Fig. 1) was built on the crest of the Schlossberg, a smaller hill closer to Schloss Pillnitz. The artificially aged structure was realized according to the principles of garden design postulated by the garden design theorist Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld. Hirschfeld is often called a ‘father of landscape garden art’.

This small painting in elongated format depicts a night view of the artificial ruin on the Schlossberg at Pillnitz. The ruin and its striking, neo-Gothic style oriel window are set against the fading glow of a sunset sky. The full moon rises amid bands of cloud. Carus’s artistic interest focuses predominantly on the realistic portrayal of contre-jour effects. Darkness pervades the structure of the ruin and its silhouette stands out against the night sky while first glints of moonlight illuminate the meadow below.

Carus made a further, somewhat larger sketch of the Schlossberg and artificial ruin in 1835 (Fig. 2). In this work the topographical position of the ruin, surrounded by dense forest, is made clear.

Fig. 2 Carl Gustav Carus, Evening Light near Pillnitz, c.1835, oil on cardboard, 13.5 x 19.6 cm, Prause 287 (?). Private collection, USA.

Carus developed a lifelong fascination with the night sky and the effects of moonlight on the landscape. This intense interest is reflected in his masterly handling of moonlight and related phenomena. It derives to some extent from the emotional power attributed to the moon in the literature and painting of the Romantic age. But it also derives in part from his own scientific research into atmospheric phenomena. He devotes a whole chapter of his theoretical writings – Briefe über Landschaftsmalerei – to what he describes as ‘moonlight pictures’.[3] He seeks to combine the Romantic synthesis of ‘sentiment’ and ‘nature’ with a determination to objectify the depiction of nature on the basis of a precise study of light conditions, interaction of colors and focus on topographical features.[4].

Where Carus most clearly reveals himself as an exponent of new artistic trends is in his landscape sketches.[5] His earliest plein-air oil sketches of the countryside around Dresden are dateable to the mid-1820s. He had probably been encouraged to sketch before the motif after seeing the oil sketches of Johan Christian Dahl, a close friend from 1817 onwards. Dahl’s plein-air oil sketches were to have foundational significance for nineteenth-century landscape painting in Germany.

All Carus’s plein-air works are consistently small in format, emphasizing their intimate character, and usually sketched on paper or cardboard. His oil studies differ from his finished studio paintings in that they display rapid, more mobile brushwork, greater compositional freedom and a certain spontaneity in the choice of motif.

This oil sketch was painted on the back of a printed card inviting Carus to attend a meeting organized by the Dresden botanical and horticultural association FLORA. Carus, like Dahl, was a member of the association and both artists occasionally used their monthly invitation cards as material for small oil sketches.

- Cited after Hans Joachim Neidhardt, ‘Zur Ambivalenz des Atmosphärischen bei Carl Gustav Carus’, in Carl Gustav Carus. Wahrnehmung und Konstruktion, Berlin 2009, p. 175.

- Like Pillnitz, Borsberg is today part of Greater Dresden.

- [Mondscheinbilder] See Carl Gustav Carus, Zehn Briefe und Aufsätze über Landschaftsmalerei mit zwölf Beilgen und einem Brief von Goethe als Einleitung, 1815-35, chap. X, Leipzig and Weimar 1982, pp. 115-9.

- See Henrik Karge, ‘Die Landschaftsbriefe von Carl Gustav Carus und ihre Rezeption in der zeitgenössischen Kritik und Kunstliteratur’, inPetra Kuhlmann-Hodick and Gerd Spitzer (eds.) Carl Gustav Carus - Wahrnehmung und Konstruktion. Essays, (Interdisziplinäres Kolloquium Dresden 2008), Berlin and Munich 2009, p. 233 ff.

- Prause, 1968, op. cit., p. 52 f.