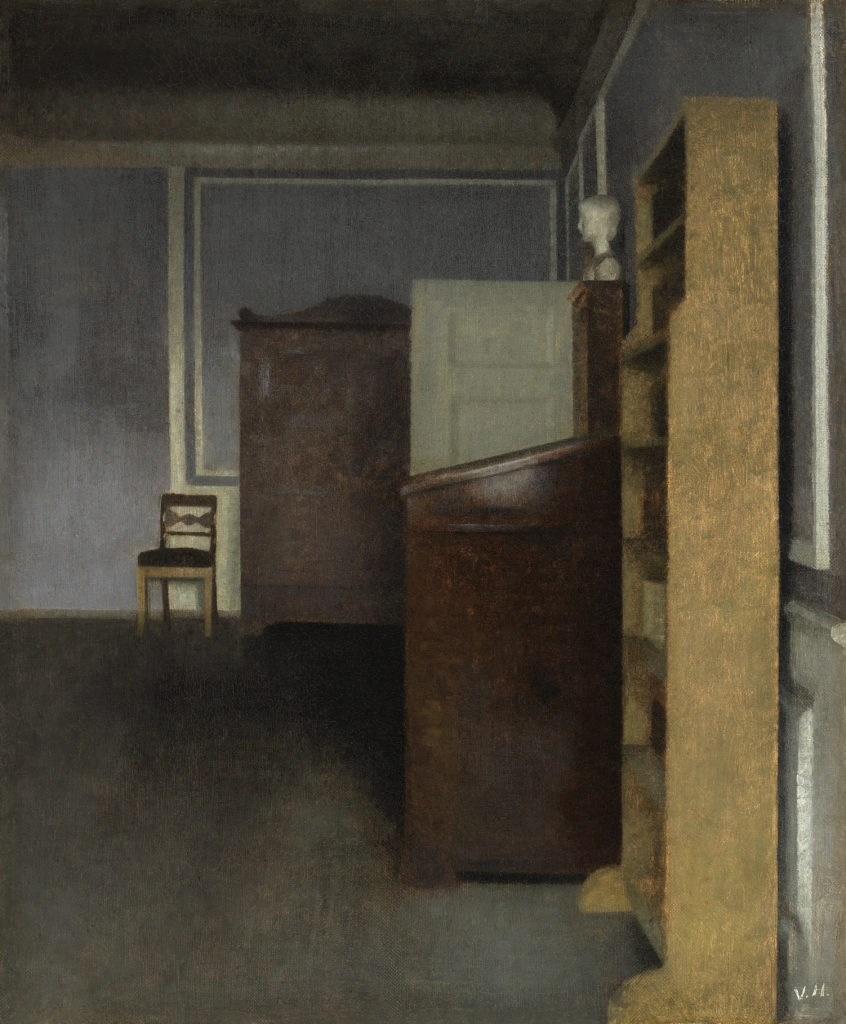

Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864 - Copenhagen - 1916)

Interior, Strandgade 30, 1905

Oil on canvas

Signed lower right V.H.

46.5 x 38.6 cm

Provenance:

Einer Koch (c.1918)[1]

Copenhagen, Kunsthallen, Købmagergade, auction 280, 1968, lot 89

Olof Sager, Malmö[2]

Exhibited:

Vilhelm Hammershøi, Göteborg, Kunstmuseum, 09.10.1999-23.01.2000, p.116,

no. 37, repr.

Vilhelm Hammershøi, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, 18.02.-07.03.2000, p.116,

no. 37, repr.

Literature:

Sophus Michaëlis and Alfred Bramsen, Vilhelm Hammershøi - Kunstneren og hans vaerk, Copenhagen and Christiana 1918, p.104, no. 271, as Stue [room] 1905

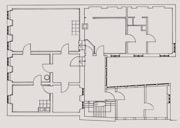

Vilhelm Hammershøi’s apartment was located on the first floor of a seventeenth-century red-brick building in

Copenhagen, Strandgade 30. He lived at this address with his wife Ida from 1898 to 1909 (fig. 1). The apartment served both as a home and as a studio.[3] He executed the present painting in the living room. This was the largest room in the apartment and was frequently used as a motif. Before moving in, the Hammershøis had the wall panelling, ornamental moulding, dado rails, windows and doors painted in a light tone. This provided a contrast with the darker tone of the floorboards and the grey of the walls and ceilings.

A newspaper interview he gave in 1907 throws light on his intentions: What makes me choose a motif is as much the lines in it, what I would call the architectural stance of the picture. And then the light, of course. It is naturally also very important, but the lines are almost what I am most taken by. Colour is of secondary importance, I suppose; I am not indifferent to how it looks in colour. I work very hard to make it harmonious. But when I choose a motif I think I mainly look at lines.[4]

The living room contains four items of furniture depicted in differing shades of brown. Their tone varies, reflecting their constituent materials and the play of light on their surfaces. All of the items were in Hammershøi’s possession. They are documented both in photographs (see fig. 2) and in other interiors painted by him.[5] The spatial organization of the composition is very subtly structured. The subject is viewed from a lowish eye-level standpoint. The verticals of the closely grouped block of furniture shown in profile against the wall at the right seem to over-emphasize the central perspective, l

ending depth to the composition. Immediately behind the furniture is a white door set at right angles. In the background is the dark shape of a mahogany armoire. The area at the left side of the composition is an empty space occupied only by the tiny silhouette of a chair set against the pale wall in the background. Light gleams on the chair’s frame and the wall behind it. Its position on the perspective line to the vanishing point subtly counter-balances the block-like concentration of the furniture on the right.

There is an emptiness to the room. It gives no insights into the lives of its occupants: Hammershøi has created a space without ‘milieu character’ and – to quote Kaspar Monrad – scraped the story away and left the core behind.[6] It is a figureless interior,[7] its surfaces and contours delicately modelled by daylight. A sombre light entering the room from a window outside the picture space somewhere behind the viewer’s standpoint tinges the contents of the room with subdued shades[8] of contrasting brown and grey. The two main elements that are highlighted are the chair – the focal point – and the near end of the tall bookcase in the foreground. This accentuation recalls a convention used in history painting where a frontally rendered figure in the foreground leads into the narrative and the composition is closed by a figure rendered from behind in the background.[9]

Yesterday I saw Hammershöj for the first time ... I am sure the more one sees of him, the more clearly one would be able to make him out, and the more one would appreciate his fundamental simplicity. I will see him again without speaking to him, since he speaks only Danish and understands very little German. One has the feeling that all he does is paint, and that this is all he is able or willing to do.

This is how Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926) described his meeting with Hammershøi in Copenhagen in December 1904. Rilke had first seen Hammershøi’s paintings at the International Exhibition staged at the Städtischer Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf and had developed a growing interest in his work. The meeting was arranged by Alfred Bramsen (1851-1932). Rilke was planning to publish an article about Hammershøi in Die Zeit and to write an essay on him. Probably rebuffed both by the brevity of the meeting and by Hammershøi’s reticent and monosyllabic manner, he was unable to go ahead with either project. The meeting gave him insufficient opportunity, he later said, ‘to gather views and insights’[10] into Hammershøi’s life and work. Rilke relocated the focus of his activities to Paris in 1905 where he worked as secretary to Auguste Rodin.

Hammershøi entered the Copenhagen Academy of Art in 1879 and completed his studies in 1885. His first exhibited painting was a portrait of a girl. This was shown at the Academy’s Charlottenborg Spring Exhibition in 1885. A painting titled Bedroom was turned down by the jury of the Academy in 1890. After that, he exhibited with the artists’ association known as Frie Udstilling [‘Free Exhibition’] set up by the Danish artist Johan Rohde. Hammershøi married Ida Ilsted (1869-1949), the younger sister of his associate and friend Peter Ilsted, in 1891. Ida was his model in a great many of his paintings of interiors. The couple travelled extensively in Europe. The influential Berlin-based art dealer Paul Cassirer (1871-1926) purchased several of Hammershøi’s paintings in 1905 and staged a solo show of his work at the Hamburg branch of his gallery. Hammershøi exhibited at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889 and again in 1900. He showed at the Venice Biennale in 1903 and at numerous exhibitions in Germany, England, Russia and the United States. After his death the contents of his studio were dispersed at an auction held on 30 October 1916. His œuvre lapsed into obscurity and was only rediscovered in the 1970s with the critical re-evaluation of Symbolism.[11]

[1] Einer Koch also owned a landscape by Vilhelm Hammershøi executed in 1909. See S. Michaëlis and A. Bramsen, Vilhelm Hammershøi - Kunstneren og hans vaerk, Copenhagen and Christiana 1918, no. 318, p.108.

[2] Olof Sager, Professor of English at the University of Lund, was an important collector.

[3] In a 1905 interview Hammershøi describes his apartment as follows: And it is important for me to be living in an apartment with a fine interior, the rooms here are very fine and ideally suited to painting. Since I was very young I have not had a proper studio. Vilhelm Hammershøi, exhib. cat., Hamburg, Kunsthalle, 22.3.-29.6.2003, p.134.

[4] Vilhelm Hammershøi, op.cit., p.135.

[5] Chair: Interior, Strandgade 30, 1908, oil on canvas, 79 x 66 cm, AROS Aarhus Kunstmuseum, Aarhus. Armoire: Interior, 1895, 97 x 70 cm. Bookcase: Interior with a Piano and a Woman, 1901, 63 x 52.5 cm, Ordrupgaard Collection, Copenhagen. Desk: Interior with a Woman at a Lectern, 1900, oil on canvas, 41 x 34.5 cm, private collection, repr. in Philipp Delerm, Intérieur. Vilhelm Hammershoi, Paris 2001.

[6] Patricia G. Berman, In another Light. Danish painting in the nineteenth century, London 2007, p.221.

[7] See Susanne Meyer-Abich, Vilhelm Hammershøi - das malerische Werk, Diss., University of Bochum, 1995, p.62. Further examples: Sunlight in the Room, 1906, David Collection, Copenhagen, 54.5 x 46.5 cm; Interior with the Artist’s Easel, 1910, 84 x 69 cm, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen.

[8] Why do I use such a reduced, delicate palette? I really do not know. It is really rather impossible for me to say anything on the subject. It comes quite naturally to me but I cannot say why. In any case, it has been that way since I first started exhibiting. The colours can probably best be described as neutral and reduced colours. I am utterly convinced that a painting achieves its best effect in a colouristic sense the fewer colours it has.

Vilhelm Hammershøi, op. cit., p.135.

[9] This can probably be interpreted as a reversion to the compositional conventions of painters such as Nicolas Poussin.

[10] Poul Vad, ‘Vilhelm Hammershøi and Rainer Maria Rilke’ in Akzente: Zeitschrift für Literatur, XLIII, 6, 1996, pp.562-71 and p.574 (the present quote).

[11] Vilhelm Hammershøi, op. cit., p.127. Hammershøi’s relationship to the Symbolist movement is ambivalent. His painting titled Artemis, exhibited with the Frie Udstilling association in 1894, has been described as ‘a key work in the history of Danish art’, symptomatic of ‘the breakthrough of the Symbolist aesthetic’. However it is unclear as to what extent Hammershøi identified himself with the Symbolists, particularly in view of his negative comments regarding a Symbolist exhibition he had visited in Paris (see Vilhelm Hammershøi, op. cit., p.14).