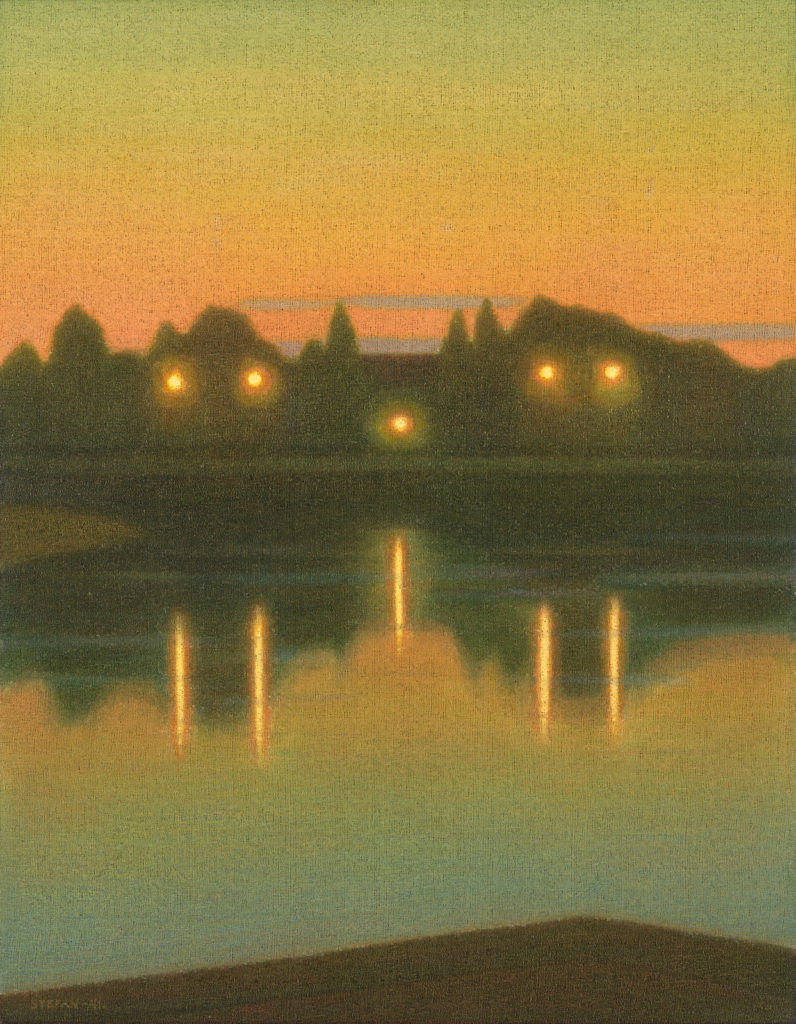

Stefan Johansson

(Vist, Östergötland 1876 - 1955 Karlstad)

Street Lights along Klarälven River, 1941

Watercolor and tempera on canvas, 47.5 x 37.1 cm

Signed and dated lower left STEFAN. -41

Provenance:

Private collection since the 1940s, Sweden

We are grateful to Dr. Stefan Hammenbeck, an expert on Stefan Johansson, for his help in compiling this entry and confirming the authenticity of the painting.

Stefan Johansson grew up in the northern part of Värmland, a landscape made world-famous by the stories of Selma Lagerlöf. At the end of the 1890s, he moved to Stockholm, attended the art academy, and continued to live there until 1931. The light effects in the nocturnal pictures of Eugène Jansson and Karl Nordström had already grabbed his interest around the turn of the century, but it was not until the early 1920s that he began to paint atmospheric cityscapes and scenes of cities lit up at night. For Johansson, the emanation of light was a spiritual phenomenon in which God’s work was revealed: darkness versus enlightenment.

In 1931, Johansson was forced by the economic crisis to move from Stockholm to Karlstad, where he moved into a modest apartment with his brother Seth and carried on painting nocturnal scenes whose sources of illumination were the moon, candles or electric light.

A new motif, which would become his main subject in the coming years, came about through his move to a house directly on the Klarälven, the river that flows through Karlstad. It was the view of the river through his window: the meditative repetition of the prospect reflected in the water, recorded at dawn and dusk and at night, unilluminated, or in the light of the streetlamps on the bridge and along the river bank. On nocturnal walks he studied the various effects of light, in order to transpose them to canvas. To this end he used a time-consuming painting technique which entailed applying watercolor directly to the unprimed canvas. In this way he was able to create soft contours, which the Italian Divisionists, whose work he had certainly seen on his trip to Italy, strove to produce by other means.

The present painting is a particularly impressive version of this motif. With the asymmetric landing stage as a repoussoir in the foreground, the reflections in the water of the streetlamps on the bridge, and the dark silhouettes of the trees in the Klara district in the background, this painting can be considered one of his masterpieces.

Johansson considered the frame an integral part of his painting, which is why he often framed his works himself, carefully choosing the color, surface structure and type of wood. The frame and painting were intended to merge into an autonomous whole.

Art critics of the time already compared Johansson with his Danish contemporary Vilhelm Hammershoi. The spirituality, the meditative repetition of the very same motifs and the ingenious painting technique prompt this comparison from our present perspective too. In addition to painting, Johansson devoted himself to philosophy and poetry. A good many of his poems assume the melancholy air of his paintings.

Even though Johansson’s work is rather curious, it can be placed in the same context as contemporaneous Scandinavian painting – just think of Eugène Jansson, the early Edvard Munch or Vilhelm Hammershoi. Introversion is something these painters have in common, and Johansson shares with Hammershoi the meditative engagement with ever-recurring motifs taken from one’s immediate surroundings.

Johansson’s spirituality is revealed in his art. He devoted himself to a type of mysticism of light. The emanation of light was, in his eyes, a timeless, divine principle. Kandinsky’s Über das geistige in der Kunst (Concerning the Spiritual in Art) and Okakura Kakuzo’s Die Ideale des Ostens (The Ideals of the East) were crucial to his artistic development. When Johansson died in 1956, Kakuzo’s book and the Bible were lying on his desk.

Johansson disliked the art academy and insisted that his academic training in Stockholm had not had any positive influence on his artistic development. Much more formative, in his view, were the journeys he made between 1909 and 1913 to Germany and especially to Italy, where he had engaged with the painting of the Renaissance and with contemporary Italian art. Works by Johansson were shown in 1911 at the large international exhibition in Rome[1] and in 1920 at the Biennale in Venice.[2]

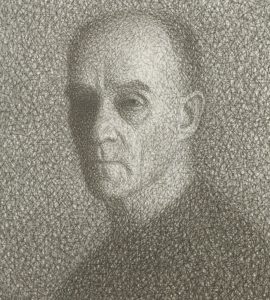

Fig. 1 Stefan Johansson, Self-Portrait, 1944, black chalk on canvas, 34,7 x 31 cm, Värmlands Museum Karlstad

It is possible that the Old Masters and fresco painting inspired Johansson to develop his unusual painting technique. At any rate, he became enthusiastic about painting in watercolor and tempera on unprimed canvas. For this purpose he used irregularly woven canvas, so-called crepe weave, without a ground, to which he applied watercolor and tempera directly. The optical effect resembles a grid and recalls the paintings of the contemporaneous Italian Divisionists, whose work he had certainly seen in Italy. The artist stuck to this time-consuming technique – which required a long period of drying between every application of paint – until the end of his career.

[1] Exposizione Internationale, Rome, 1911. [2] L'Esposizione internazionale d'arte, Biennale di Venezia, XII, 15 April - 31 October 1920.