Pietro Antonio Rotari

(Verona 1707 - 1762 St. Petersburg)

Russian Girl with a Muff, 1752-6

Oil on canvas, 45.2 x 34.5 cm

Provenance:

Commissioned by: either Maria Josepha of Saxony, Dauphine of France, daughter of August III, Christian Ludwig von Hagedorn or Earl Ignaz Accoramboni.[1]

Private collection, Germany

Professor Gregor Weber of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, has kindly confirmed the authenticity of the painting on the basis of a photograph. We thank him for his assistance.[2]

Rotari’s central preoccupation as a painter was how to evoke his sitters’ moods and portray their personal characteristics. His approach drew on theories advanced by Le Brun in his instructions for the representation of passions and emotions.[3] Rotari’s numerous portraits of men and women at different stages of life are thus autonomous works of art. Similar portrait series, known as varie teste, were already common among contemporary printmakers.

Fig. 1 Mikhail Shibanov, Empress Catherine II in Traveling Dress, 1787, St. Petersburg. The Russian Empress wears a similar Hungarian hat.

Rotari’s portraits of young women can be read as an erotically charged game. Both viewer and subject abandon themselves to the illusory game of observing and being observed, to the extent that image and reality become blurred. The young woman looking directly at the viewer, the fur-trimmed muff covering her mouth and décolletage, her lips touching the fur: what a masterly staging of sensuousness!

The fur-trimmed hat worn by our model was in vogue in Russia in the second half of the eighteenth century. At the tsar’s court, such a hat, derived from a Hungarian costume, soon became a fashionable piece of headgear that was also worn by Empress Catherine II (fig. 1).

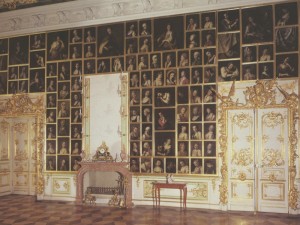

Fig. 2 Rotari Portrait Gallery in Peterhof Palace, St. Petersburg

The majority of Rotari’s portrait series both for the Royal Court of Saxony in Dresden and for Empress Elizabeth of Russia at the Peterhof Palace in St. Petersburg are still extant. The ‘Rotari Hall’ at Peterhof Palace (fig. 2) is still intact, giving art historians some idea of the now-lost hanging system originally in place in Dresden too. Upon Rotari’s death, Catherine the Great acquired most of the portrait heads in his estate with the intention of using the 368 paintings to decorate a vast hall in the palace[4] known as the Cabinet of Manners, Customs, Morals and Passions.[5] The portraits were hung frame-to-frame, separated only by delicate strips of gilt framing, within elaborate boiserie.

The present painting was intended for the picture gallery in Dresden or St. Petersburg. This thesis is supported by the presence of the same thinly applied ochre framing line found in other Dresden portraits. The framing line was necessary in order to install the paintings in accurate, grid-like juxtaposition within the boiserie.

Rotari trained in Verona and was also in Venice for a time. Records show that from 1727 onwards he was working in Rome, where his style began to develop a more ‘consistent form of classicism’.[6] He entered the studio of Francesco Solimena in Naples in 1729 and went on to open his own private academy of painting in Verona in 1734. He was elevated to the aristocracy and given the title of conte in 1749 in recognition of his artistic achievements. In 1750 he visited Vienna, where he executed a number of religious paintings for the Imperial Court. Here he was able to study the work of Jean-Étienne Liotard. He visited the Royal Court of Saxony in Dresden in 1752-53. While in Dresden, he presented twelve of his varie teste to Maria Josepha of Saxony, Dauphine of France. He did not, however, choose to travel to France, but instead took up an invitation from Elizabeth I of Russia to visit St. Petersburg in 1756. The extraordinary success of his portrait of the Empress brought him an appointment as court painter, a privileged position that he enjoyed only briefly before dying suddenly in 1762.

[1] Information provided by Prof. Gregor Weber, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

[2] ‘Opinions concerning works of art are given by the staff of the Rijksmuseum to the best of their knowledge. Such opinions remain the intellectual property of the museum, and may be made public or repeated only with written authorization from the Rijksmuseum. Opinions will be offered at the request of bona fide owners of works of art or their legal representative. The Rijksmuseum and individual members of its staff take no responsibility whatsoever for any inaccuracies or omissions in their statements, nor for any consequent losses to third parties nor for any claims that may arise.’

[3] Charles Le Brun’s Conférence [...] sur l’expression générale et particulière des passions is specifically addressed to painters. The first edition, illustrated by Le Brun, appeared in 1696. The work ran to several editions, one of which appeared in Verona in 1751, shortly before the present painting originated.

[4] For biographical details, see Gregor J. M. Weber, Pietro Graf Rotari in Dresden. Ein italienischer Maler am Hof König Augusts III. Bestandskatalog anläßlich der Ausstellung im Semperbau, exhib. cat., Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Emsdetten/Dresden 1999, pp. 7-15.

[5] G. K. Nagler, Neues allgemeines Künstler-Lexicon, XIII, Munich 1843, p. 463.

[6] Weber, op. cit., p. 7.