Emil Orlik (Prague 1870 - 1932 Berlin)

Landscape with Mount Fuji in the Distance, 1908

Oil on canvas, 120.5 x 154.5 cm

Signed and dated lower left in red E·ORLIK·08·

We are grateful to Dr. Birgit Ahrens and Dr. Agnes Matthias for their advice on aspects of Emil Orlik’s work and his travels in Japan.

Emil Orlik’s avid interest in Japanese art in general and local landscapes in particular was shared by many of his contemporaries. Interest had originally been sparked by the arrival in Europe of Japanese art and artefacts – particularly, woodblock prints – in the mid-nineteenth century. This had been made possible when Japan started to open its ports to trade with the West. Orlik differed from the majority of his contemporaries in that he did not confine himself to appreciation of the artistic merits of Japanese art alone. He was intent on immersing himself in Japanese culture and wanted to learn the techniques of Japanese woodblock printing from Japanese masters in Japan. He was one of the first European artists to travel to Japan in the early 1900s, matching Gauguin and Nolde in his determination to explore unknown worlds and experience different cultures. His ten-month artistic apprenticeship[i] in Japan was to leave an indelible stamp on his later oeuvre.[ii] He was later seen to be something of a ‘missionary of a true East Asian culture’.[iii]

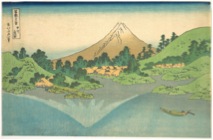

In 1854, Japan, bowing to Western pressure, took the first steps towards abandoning its isolationist policies. These had lasted for over two hundred years under Edo rule. International trade expanded rapidly and Japanese works of art started to flow into Europe. Their influence gradually began to penetrate European art, with colour woodblock prints the central focus. A display of Japanese art and design at the third Paris World’s Fair of 1878 was much feted. The display – featuring landscapes by Utagawa Hiroshige, courtesan prints by Kitagawa Utamaro and Katsushika Hokusai’s images of Mount Fuji – triggered a surge in the collection and appreciation of Japanese art. Hokusai’s Fuji landscapes provided a direct source of inspiration for Orlik’s depiction of the peak. Félix Vallotton, Edouard Manet and Edgar Degas were all to adapt formal elements of Ukiyo-e[iv] colour woodblock print design, especially the one-point perspective, the absence of modelling and the stylised emphasis on linearity. Orlik had taken up the study of Japanese art before his journey to Japan and its influence is seen in his work even at that stage. He was a contributor to the development of Japonisme, a cultural trend which emerged in the 1860s and which was to exert a profound influence on Western art.

Orlik first visited Japan in 1900 and initially, he was to experience a degree of disillusionment in Tokyo. The ambitious programme of westernisation and economic modernisation initiated by the new Meiji leadership was so far advanced that it obscured much of the traditional Japan he had expected to find. However, all this changed when he left Tokyo for Kyoto in late September 1900. On the way, he stopped at Kamakura, Enoshima and Hakone. Hakone was noted for its hot springs, and particularly for the beauty of its autumn foliage and its striking views of Mount Fuji. It was on these excursions further inland that he was to discover the Japan of old. He recorded his impressions in sketches which served him as aide-memoires for later prints and paintings.[v]

The present, vibrantly coloured autumn landscape focuses on a distant view of Mount Fuji. Dated 1908, it is a recently discovered work of considerable importance and a major addition to Orlik’s known oeuvre. In it, he focuses on the outstanding natural beauty of Japan. His debt to Japanese art is clearly evident in the flatness, the decorative effect and the high degree of stylisation, combined with the raised viewpoint and formal arrangement of the composition in brilliant patches of colour dispensing with shadow.

Elements of the painting are linked thematically both to the etching titled Mount Fuji near Hakone, executed in 1921 (Fig. 1), and to the 1901 etching titled Evening.[vi] The motif of two female figures standing under a tree recalls a motif sketched by Orlik on a postcard addressed to his friend Max Lehrs in 1900 (Fig. 2). A Japanese model for the present painting has not been identified. Nevertheless, parallels with Katsushika Hokusai’s colour woodblock series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei, c.1830-5) are clear. Orlik has chosen to draw on Hokusai’s print, [Reflection in the] Surface of the Water at Misaka in Kai Province (Kōshū Misaka suimen) (Fig. 3),[vii] likewise placing Mount Fuji, reflected on the surface of the lake, at the centre of the composition.

Fig. 3 Katsushika Hokusai, [Reflection in the] Surface of the Water at Misaka in Kai Province, c.1834, colour woodblock print, 24.4 x 37.5 cm

Orlik was born in Prague and moved to Munich in 1891 to begin his studies. He worked with Bernhard Pankok, a fellow student and friend, to develop experimental printmaking techniques. In 1899 he joined the Vienna Secession. His first print series, a set of woodcuts titled Kleine Holzschnitte, was published in 1900. As noted, he set off on his first visit to Japan in the same year. In 1904, he moved his studio from Prague to Vienna where his intense preoccupation with Japanese woodblock printing was to have a groundbreaking impact on the Vienna Secession. In 1905, he was appointed professor of graphic art and book illustration at the Academy of the Museum of Applied Arts in Berlin. He settled in Berlin, playing a leading role in the Berlin Secession. He quickly built on his success in Vienna to forge a career as a painter, printmaker, society portraitist and stage designer.

[i] […] als lernender Künstler. See Peter Voss-Andreae (ed.), Emil Orlik in Japan. Wie ein Traum!, exhib. cat., Hamburg, Museum für Kunst & Gewerbe, Hamburg 2012, p. 12.

[ii] Although he travelled to Japan a second time in the winter of 1911, returning in 1912, this second visit was to have little impact on his artistic work.

[iii] […] eine Art Missionär einer ‘wahren’ ostasiatischen Kultur. See Agnes Matthias (ed.), Zwischen Japan und Amerika. Emil Orlik, ein Künstler der Jahrhundertwende, exhib. cat., Kunstforum Ostdeutsche Galerie Regensburg, Bielefeld 2013, p. 20. Following his return from Japan he lectured frequently on his travels and experiences in Japan, wrote articles for the magazine Ver Sacrum and published a 16-part portfolio of prints titled Aus Japan. He also formed his own collection of Japanese woodblock prints. He exhibited widely nationally and internationally. His work was also shown in Japan.

[iv] Ukiyo-e, literally ‘pictures of the floating [i.e. fleeting] world’, had a major influence on western art in the second half of the nineteenth century. This style of Japanese woodblock print had already reached a high level of development in the mid-seventeenth century. See Matthias, op. cit., p. 14.

[v] See Setsuko Kuwabara, ‘Emil Orlik und Japan’, Heidelberger Schriften zur Ostasienkunde, VIII, Frankfurt am Main 1987, pp. 88-92. While a large body of prints by Orlik with Japanese motifs are preserved, only a very few paintings on Japanese themes are still extant. A small number are documented in letters and publications. One recorded example is a set of four landscapes - a mountain view, a garden, a mountain lake and a waterfall. See Hans Singer, ‘Emil Orlik - Wien. Otto Eckmanns Nachfolger in Berlin’, in Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, XV, Darmstadt 1904-5, pp. 376-7.

[vi] Emil Orlik, Evening, 1901, plate 12 from the portfolio Aus Japan, etching, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Department of Prints and Drawings.

[vii] Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), [Reflection in the] Surface of the Water at Misaka in Kai Province, c.1834, colour woodblock print, 24.4 x 37.5 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, inv. JP2969.

[viii] Orlik’s visit to Japan in 1900 is well documented in his letters to Max Lehrs. Lehrs was then working as curatorial assistant at the Department of Prints and Drawings in Dresden.

[ix] Kunstchronik. Wochenzeitschrift für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, NF 20 (1909), p. 203.

[x] See Birgit Ahrens, ‘Denn die Bühne ist der Spiegel der Zeit’. Emil Orlik (1870-1932) und das Theater, Kiel 2001.