Pietro Antonio Rotari (Verona 1707 - 1762 St. Petersburg)

Boy Sleeping, Dresden, 1753-6

Oil on canvas, 43.5 x 34 cm

Provenance:

In all probability commissioned by Augustus III, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony (1696-1763)

Galerie Adrien Guéry, Paris

Private collection, France (since 1917)

Professor Gregor Weber of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, has kindly confirmed the authenticity of the painting on the basis of a photograph. We thank him for his assistance.[1]

The close physical proximity of the sleeping boy to the observer and the intimacy of the moment lend the painting something of a voyeuristic quality. The boy’s cheeks are flushed and there is a ghost of a smile on his lips. He is still half in and half out of his brown jacket and appears to have been overcome by sleep while removing it. Pietro Antonio Rotari, a master of character portraiture, has spared no detail in his depiction of the boy’s eyelashes and mouth. Particularly striking is the focus on the angle of the head and the concentration of light on the face.

Rotari’s central preoccupation as a painter was to investigate how to reveal the inner mood of his sitters and to portray their personal characteristics, expressing all this in their facial features. His approach drew on theories advanced by Le Brun in his instructions for the representation of passions and emotions.[2] The numerous portraits Rotari produced depicting men and women at different stages of life are thus autonomous works of art in their own right. Similar portrait series were already common among contemporary printmakers. They were known as varie teste – and Rotari set out to develop the basic idea in the medium of painting.

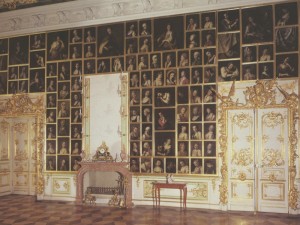

The majority of Rotari’s portrait series both for the Royal Court of Saxony in Dresden and for Empress Elizabeth of Russia at the Peterhof Palace in St. Petersburg are still extant. The ‘Rotari hall’ at Peterhof Palace (Fig. 1) is still preserved, enabling art historians to have some idea of the hanging system originally in place in Dresden but which is now lost. On Rotari’s death, Catherine the Great acquired most of his portrait heads from the artist’s estate. Her intention was to use the 368 paintings to decorate one of the vast halls of the palace[3] known as the Cabinet of Manners, Customs, Morals and Passions.[4] The portraits were hung frame-to-frame, separated only by delicate strips of gilt framing, within elaborate boiserie. One of the portraits on the east wall of the hall is a replica[5] of the present painting, although in a different format and executed in a different palette.

This painting was almost certainly executed for the picture gallery in Dresden. This thesis is supported by the presence of the same thinly applied ochre framing line found in other Dresden portraits. The framing line was necessary in order to fit the paintings in accurate, grid-like juxtaposition within the boiserie. In addition, the format of the present painting precisely matches one of the formats chosen for the Dresden portraits.

Rotari trained under the Flemish engraver Robert van Audenaerdt in Verona. His later apprenticeship to Antonio Balestra was to have a greater formative influence on his work. He was in Venice for a time and records show that he worked in Rome from 1727 onwards. It was here that his style began to develop a more ‘consistent form of classicism’.[6] He entered the studio of Francesco Solimena in Naples in 1729 and went on to open his own private academy of painting in Verona in 1734. He was elevated to the aristocracy and named a conte in 1749 in recognition of his artistic achievements. In 1750 he visited Vienna, where he painted a number of religious paintings for the Imperial Court. Here he had access to and was able to study the work of Jean-Étienne Liotard. He visited the Royal Court of Saxony in Dresden in 1752-3. While in Dresden, he presented twelve of his varie teste to Maria Josepha of Saxony, Dauphine of France. He did not, however, choose to travel to France, but instead, in 1756, took up an invitation from Elizabeth I of Russia to visit St. Petersburg. The extraordinary success of his portrait of the Empress brought him an appointment as court painter, a privileged position that he was to enjoy only briefly. He died suddenly in 1762.

[1] ‘Opinions concerning works of art are given by the staff of the Rijksmuseum to the best of their knowledge. Such opinions remain the intellectual property of the museum, and may be made public or repeated only with written authorization from the Rijksmuseum. Opinions will be offered at the request of bona fide owners of works of art or their legal representative. The Rijksmuseum and individual members of its staff take no responsibility whatsoever for any inaccuracies or omissions in their statements, nor for any consequent losses to third parties nor for any claims that may arise.’ [2] Charles Le Brun’s Conférence [...] sur l’expression générale et particulière des passions is specifically directed to painters. The first edition – with illustrations by Le Brun – appeared in 1696 and the work ran to several editions. One of these was an edition published in Verona in 1751 – very shortly before the date of execution of the present painting. [3] For biographical details, see Gregor J. M. Weber, Pietro Graf Rotari in Dresden. Ein italienischer Maler am Hof König Augusts III. Bestandskatalog anläßlich der Ausstellung im Semperbau, exhib. cat., Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Emsdetten/Dresden 1999, pp. 7-15. [4] G. K. Nagler, Neues allgemeines Künstler-Lexicon, XIII, Munich 1843, p. 463. [5] Oil on canvas, 45 x 55 cm, St. Petersburg, Peterhof Palace, east wall, repr. in Marco Polazzo, Pietro Rotari: pittore veronese del Settecento (1707-1762), Negrar 1990, p. 126, no. 232. [6] Weber, op. cit., p. 7.