Derick Baegert

(c.1440 - c.1509 Wesel)

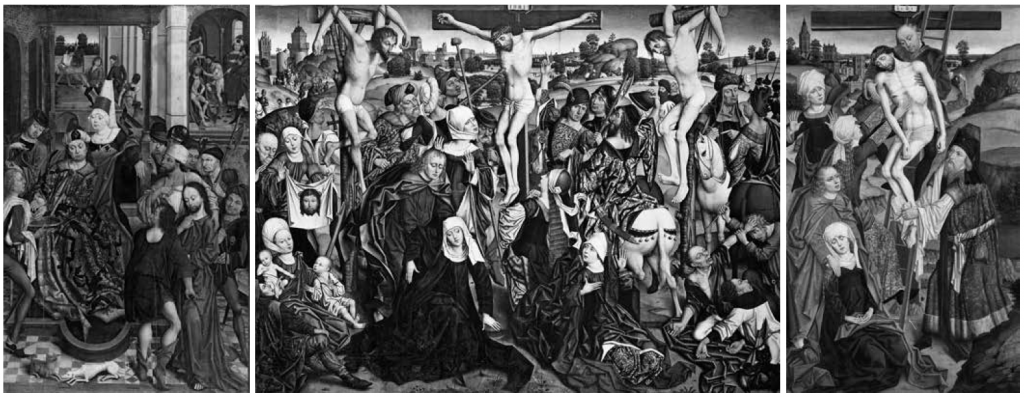

The Descent from the Cross, c.1480-90

Oil on an oak panel constructed of five vertical boards, the one to the very right replaced prior to 1819, 158 x 97 cm, 158 x 97 cm

Provenance:

Canon Franz Pick (1750-1819), Cologne/Bonn[1] (Pick also owned a second panel, the back of the present work – the original panel was divided to separate the scenes of the Descent from the Cross and, on the back, Blessed Gertrude of Altenberg distributing Alms)

Bonn, auction sale, the collection of Franz Pick,[2] 27 August 1819 (as ‛Rogier van der Weyden’), sold for 300 ducats

Carl von Behr-Negendank, Semlow near Franzenburg (1791-1827)[3]

Ulrich von Behr-Negendank (1826-1902), son of the above (appointed president of the administrative district of Stralsund in 1869)

Thence by descent in the Behr-Negendank family

Stralsund Museum (from 1946)

Restituted to the Behr-Negendank family

German private collection

Literature:

August von Arnswaldt, ‛Ueber altdeutsche Gemälde’, in Wünschelruthe – Ein Zeitblatt, Göttingen 1818, pp. 147-8

Edit Karbe, Die Kreuzabnahme im Stralsunder Museum - ein Beitrag zur Derick Baegert-Forschung, degree thesis, Humboldt University of Berlin, 1955

Joachim Fait, ‛Die Kreuzabnahme in Stralsund und ihre Bedeutung im Werk des Derick Baegert’, in Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch, XX, 1958, pp. 261-74

Walther Scheidig, Unbekannte Meisterwerke der Malerei: Schätze aus kleinen und mittleren Sammlungen Ostdeutschlands, Munich 1965, p. 26

Paul Pieper, ‛Eine unbekannte Stadtansicht von Derick Baegert’, in Westfalen. Hefte für Geschichte, Kunst und Volkskunde, LI, 1973, p. 133, fig. 50

Jürgen Becks and Martin Wilhelm Roelen (eds.), Derick Baegert und sein Werk, exhib. cat., Städtisches Museum Wesel, Wesel 2011, p. 129, plate XXVIII

Paul Pieper, Die deutschen, niederländischen und italienischen Tafelbilder bis um 1530, (collection catalogue), Westfälisches Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kultur Münster, Münster 1990, p. 343

Ferne Welten - Freie Stadt: Dortmund im Mittelalter, exhib. cat., Museum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte der Stadt Dortmund, Dortmund 2006, p. 192

Records of the Lower Rhenish painter Derick Baegert’s[4] life show him principally active in Wesel in the years 1440 to 1509. Baegert ranks as one of the leading painters of the late fifteenth century working in north-west Germany. Recent research findings have established that he was active in the border region between Westphalia, the Lower Rhine and the southern Netherlands.[5] Stylistically, his work lies at the point of transition between the Late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance period.

A decisive renewal of northern European painting started out from the Burgundian Netherlands in the mid fifteenth century – the emergence of a new tradition often known by the term ars nova (new art). Jan van Eyck (c.1390-1441), the ‛Master of Flémalle’ (active 1410-1440) and Rogier van der Weyden (probably 1399-1464) were the forerunners of the ‘new art’. They endowed their figures with sculptural solidity and portrait character, creating spatial and perspectival impact, and refined effects of light and shadow. This was helped by the capabilities of the recently discovered new paint medium, oil, with its advantages over conventional tempera paints. By applying multiple layers of glazes the artist could achieve a pictorial effect that satisfied the new quest for realism.[6] Ars nova lent heightened reality to the portrayal of salvation and therefore enabled the viewer to experience higher empathy in his reception of both image and belief – devotio moderna (new piety).[7]

Baegert is generally thought to have been born shortly before 1440 as the son of a merchant from Wesel, Johan Baegert, and his first wife Mechtelt Myrneman. In the late Middle Ages, Wesel flourished as a center for architecture, painting and sculpture. Thriving artistic production under the patronage of the Burgundian court was to have a evident impact on Baegert’s work. However it is unclear whether he learned from primary sources during his years of travel, or whether he acquired his knowledge via other, more indirect sources such as prints. A visit to the Burgundian Netherlands cannot be ruled out. It is also possible that he looked to the work of the Dortmund painter Conrad von Soest (c.1370-after 1422) for guidance. In 1464, Baegert established his own household and a workshop in Wesel. His first major work, executed between 1468 and 1476, was commissioned by John I, Duke of Cleves (1419-81) for the high altar of the Dominican Church in Dortmund. It is now in the Propsteikirche in Dortmund.

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Duchy of Cleves, to which the Hanseatic city of Wesel belonged, enjoyed an economic and cultural renaissance. The Duke had grown up in Brussels at the court of his uncle, Philip of Burgundy (Philip the Good) and was almost certainly conversant with the artistic ideas promoted there, as with the work of its most celebrated figurehead, Rogier van der Weyden. On that basis it can be assumed that Baegert’s fundamental artistic approach harmonized well with that of his monarch.

Records show that in 1476 Baegert began to undertake artistic commissions in his home town of Wesel. One of these was the retable for the high altar in the Matenakirche, executed between 1477 and 1482. Fragments of the altarpiece are now in the collection of the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. One of his final works, a retable depicting scenes from the Passion, was commissioned by the Mayor of Cologne, Gerhard van Wesel (d.1510). Fragments of this are now held in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich and in the Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique in Brussels.[8] After 1509, there are no further records. Baegert’s son Jan (c.1465–c.1535) continued to conduct business from his father’s workshop in Wesel.

In the 1930s, scholarly research into Baegert’s work reached its first high point, culminating in an exhibition dedicated solely to Baegert staged in Münster in 1937. The LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur in Münster now holds the largest collection of paintings by Baegert.[9] The existence of the present panel representing the Descent from the Cross, painted in circa 1480-90, first became known a good many years later – mainly through the article published by Joachim Faits in 1958.

This vertical-format panel depicts the moment in which Christ’s body is taken down from the cross. The viewer witnesses the act of lowering the body. Joseph of Arimathaea stands on a ladder supporting the upper part of Christ’s upright body while Nicodemus swathes the feet in a linen sheet. Mary Magdalene leans forward with outstretched arms to take some of the weight, placing her right foot on a rung of the ladder. Baegert’s depiction of the pressure of her fingers on Christ’s body, creating tiny folds in the skin, is entirely realistic. The Virgin kneels at the foot of the cross, supported in her suffering by St. John. The female figure raising her hands in a gesture of mourning is Maria Salome, one of the Three Maries. In the middle ground are the diminutive figures of St. John and the Virgin on the road to Golgotha. An expansive stretch of ocean is glimpsed in the background, flanked at the left by the pinnacles and towers of a northern European town built in an architectural style typical of the period, and probably intended to represent Jerusalem.

The palette is rich and the dominant colors – red, green and blue – form a contrast to the pallidity of Christ’s body, and to the shroud and the headdresses of the women. With his rendering of the sumptuous brocades and fur-edged robes that mirror courtly fashion of the period Baegert demonstrates the pinnacle of his virtuosity as a painter. A number of the brocade robes are fashioned illusionistically using the Pressbrokat (embossed brocade) technique. Their surfaces were overlaid with gold leaf and are modeled in high relief against the gold ground. Elaborate relief decoration embossed into the gold creates a highly deceptive imitation of the haptic and optical qualities of true brocade.[10]

Baegert produced a number of versions of the Descent from the Cross and the scene immediately following this, the Lamentation. There is a very close relationship between the present panel and the depiction of the Lamentation now in the collection of the Westfälisches Landesmuseum in Münster. Here, the figures of the Virgin and St. John are placed at the right, virtually a mirror image of the group in the present panel. The figures of Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathaea are largely identical in terms of figure type and dress.[11] Baegert almost certainly found models among the works of Rogier van der Weyden. Joachim Fait explicitly cites a panel by an artist in the circle of Rogier van der Weyden now held at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich.[12] Recent studies have found that van der Weyden’s influence was most probably indirect and Baegert is more likely to have gained exposure to his work through drawings, possibly engravings (the prints of Israhel von Meckenem, for example), and perhaps paintings by other artists.[13]

As Joachim Fait has posited, the present painting represents the interior of the right-hand wing of a large, winged retable of unknown origin depicting scenes from the Passion. The central panel, a depiction of the Calvary, was probably destroyed by fire in Berlin in 1945. When the outer wings were opened, three scenes were revealed. The interior of the left-hand wing represented Pilate Washing his Hands and the interior of the right-hand wing, the Descent from the Cross (the present panel). The two images faced each other. When both outer wings were closed, two different scenes were revealed – on the back panel at the left, a representation of the Birth of Christ and on the back panel at the right, Blessed Gertrude of Altenberg distributing Alms (see the proposed reconstruction of the retable, Figs. 1-5).

Fig. 1 Pilate Washing his Hands, oil on oak panel, 159.5 x 99 cm, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, inv. Gm37[14]

Fig. 2 Calvary, oil on panel, 157 x 214 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, inv. 1194, now lost (probably destroyed by fire in the Friedrichshain bunker in May 1945)[15]

Fig. 3 The Descent from the Cross, oil on oak panel, 158 x 97 cm, with Daxer & Marschall Kunsthandel, Munich

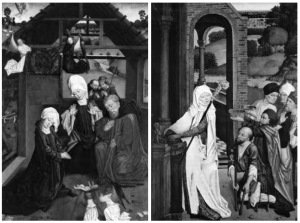

Fig. 4 The Adoration, oil on oak panel, 157 x 99 cm, private collection[16]

Fig. 5 Blessed Gertrude of Altenberg distributing Alms, on oak panel, 158 x 97 cm, Museum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Dortmund, inv. C 5030[17]

Compelling new evidence has emerged, adding weight to Joachim Fait’s hypothesis. Exact measurements have very recently been taken. These indicate that the panels representing Blessed Gertrude of Altenberg distributing Alms and the Descent from the Cross at one time almost certainly formed the two sides of a single panel.[18] It is likely that the original panel, sharing the fate of so many other panels, was divided during secularization. The two paintings are documented in the 1818 inventory of the renowned collection of Canon Franz Pick in Cologne – not as one panel but as two, with separate entries and extensive individual descriptions.[19]

[1] Franz Pick was initially private secretary to Provost Franz Wilhelm von Oettingen-Baldern in Cologne. Pick was a friend of Ferdinand Franz Wallraf, the Cologne art collector. They are said to have shared ownership of a number of artworks. When Pick moved to Bonn in 1805, they were obliged to separate their possessions. This led to the rupture of their friendship. See Alexandra Nebelung, ‛Wallraf als Sammler: Einflüsse und Entwicklung’, in Gudrun Gersmann and Stefan Grohé (eds.), Ferdinand Franz Wallraf (1748-1824) — Eine Spurensuche in Köln:

http://wallraf.mapublishing-lab.uni-koeln.de/sammeln-um-1800/beispiele-der-koelner-sammlungspraxis/wallraf-als-sammler-einfluesse-und-entwicklung (accessed 16.01.2018).

[2] See A.G. Spiller, Kanonikus Franz Pick: ein Leben fuer die Kunst, die Vaterstadt und die Seinen, inaug. diss., Bonn 1967, pp. 119-28 and appendix, pp. 133-48. Cited in J. Grave, „Der ideale Kunstkörper“: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe als Sammler von Druckgraphiken und Zeichnungen, Göttingen 2006, p. 175, footnote 649. Goethe also attended the auction.

[3] Ulrich Graf Behr Negendank (ed.), Urkunden und Forschungen zur Geschichte des Geschlechts Behr, V: Nachträge von 1138 bis 1446, Mit einer Kunstbeilage und Register, Berlin 1894.

[4] For almost a century, an important body of work now irrefutably given to Derick Baegert was associated by scholars with the name ‛Duenwege’. This was due to the incorrect interpretation of a mention in a sixteenth-century chronicle. For up-to-date research findings, see Martin Wilhelm Roelen, ‛Achtzig Jahre Derick-Baegert-Forschung. Biographie eines spät entdeckten Malers’, in Jürgen Becks and Martin Wilhelm Roelen (eds.), Derick Baegert und sein Werk, exhib. cat., Städtisches Museum Wesel, Wesel 2011, p. 11.

[5] See Till-Holger Borchert (ed.), Van Eyck bis Dürer: Altniederländische Meister und die Malerei in Mitteleuropa, exhib. cat., Groeningemuseum, Bruges 2010.

[6] See Jochen Sander, ‛Die “ars novaˮ und die europäische Malerei im 15. Jahrhundert’, in Stephan Kemperdick and Jochen Sander (eds.), Der Meister von Flémalle und Rogier van der Weyden, exhib. cat., Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main and Gemäldegalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, Frankfurt am Main and Berlin 2008, pp. 31-7.

[7] See Petra Marx, ‛Derick Baegert. Ein spätmittelalterlicher Maler in Wesel und sein Schaffen zwischen Niederrhein, Niederlande und Westfalen, Forschungsstand und offene Fragen’, in Derick Baegert und sein Werk, op. cit., pp. 51-2.

[8] Derick Baegert, The Lamentation, after 1498, oak panel, 132.9 x 79.3 cm, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek, Munich, inv. WAF 224;

Derick Baegert, Calvary, after 1498, oak panel, 131.7 x 168.7 cm, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek, Munich, inv. 223;

Derick Baegert, Christ before Pilate, oak panel, 132 x 78.5 cm, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels, inv. 4916;

Derick Baegert, Six Apostles with Gerhard van Wesel, oak panel, 132 x 78.5 cm, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels, inv. 6586.

[9] LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur Münster.

[10] Annemarie Stauffer, ‛Prachtvoll und bedeutungsreich: Seidengewebe in der Tafelmalerei des 15. Jahrhunderts am Beispiel der Sammlung des Landesmuseums in Münster’, in Westfalen 85/86, Münster 2007-8 (2010), p. 258.

[11] Derick Baegert, The Lamentation, c.1480-90, mixed media on oak panel, 123 x 95 cm,

Westfälisches Landesmuseum, Münster, inv. 1047 LM.

[12] Circle of Rogier van der Weyden, The Descent from the Cross, c.1430, oil on oak panel, 57.3 x 52.5 cm, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek, Munich, inv. 1398.

[13] See Stephan Kemperdick, ‛Westfalen und die Küstenregion’, in Van Eyck bis Dürer, op. cit.,

pp. 221-9.

[14] We would like to thank Dr. Daniel Hess, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, for providing this information. The width of the planks at the top (from left to right) is: 18.9 / 21,2 / 19.3 / 19.8 / 20.6 cm; and at the bottom: 17.2 / 24.9 / 20.5 / 20.7 / 16.5 cm (14 December 2017).

[15] Rainer Michaelis, Gemäldegalerie: Verzeichnis der verschollenen und zerstörten Bestände der Gemäldegalerie Berlin, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz: Dokumentation der Verluste, Berlin 1995, p. 28, no. 1194.

[16] The panel representing The Adoration was held at the Ludwig Roselius Museum in Bremen until 1988 and is now in a private collection. We would like to thank Claudia Klocke of the Böttcherstraße Museums in Bremen for providing this information (24 January 2018).

[17] We would like to thank Dr. Brigitte Buberl, Museum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Dortmund, for providing this information (18 January 2018).

[18] Joachim Fait’s hypothesis is corroborated by measurements that have recently been taken of the two panels and the planks they were made of. The Descent from the Cross, now with Daxer & Marschall, Munich and the Dortmund Blessed Gertrude of Altenberg distributing Alms (Museum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte), do indeed constitute the two sides (interior and back) of the right-hand wing of a retable.

[19] August von Arnswaldt, ‛Ueber altdeutsche Gemälde’, in Wünschelruthe – Ein Zeitblatt, Göttingen 1818, pp. 147-8: Of some noteworthiness are two large pictures, their style being of somewhat greater severity, one of which representing a saintly abbess seen to offer alms to the needy; amongst whom are shown a number of very fine visages that surely recall Hemmelink, yet for him the painting, in style with some mark of instruction, displays too little firmness of principle, too little grace and too little care for execution; indeed we do not believe him to have painted such large figures. Of the other painting the same may be said, a descent from the cross which in respect of its color displays certain virtues, albeit also lacking in harmony. The body of Christ, loosened from the cross by a man, is received by the Magdalene from below with rigidly outstretched arm, while the body’s feet are clasped by Joseph of Arimathaea: in the foreground, the Virgin lies in a swoon, unseeing, her hands resting in her lap; at her back St. John, supporting her, his tear-filled eye gazing towards the cross. A beauteous, most affecting sorrow prevails over the scene, yet there lies over single parts a wincing pain that troubles the viewer; in this work, too, the utterance is manifold and truthful, individual visages, notably Joseph of Arimathaea, are most admirably drawn; yet the landscape is indifferent and the aerial perspective flawed.